OK, this is the final pool of images and info you should review for Tuesday's final. See you then!

Unity and Balance

Piero della Francesca's The Flagellation, c. 1469, a 23 x 32” oil and tempera painting on wood panel, achieves unity by balancing the geometrical precision of the architectural perspective against the organic forms of the human bodies and clothing, the deep spatial illusion on the left with the foregrounded figures on the right, and the dramatic emotional content of the flagellation with the calm and orderly overall structure and contemplative attitude of the three most prominent characters.

"In his print “The Great Wave off Shore at Kanagawa,” Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) created a unified composition by organizing repetitions of shapes, colors, textures, and patterns to create a visual harmony even though the scene is chaotic. These repetitions visually link different parts of the picture. Even Mount Fuji, in the middle of the bottom third of the work, almost blends into the ocean: because whitecaps on the waves mimic the snow atop Mount Fuji, the mountain’s presence is felt and reiterated throughout the composition. The shape and placement of the boats also create a pattern amongst the waves. Because the great wave on the left is not repeated, it has a singular strength A that dominates the scene. Hokusai has also carefully selected the solids and voids in his composition to create opposing but balancing areas of interest. As the solid shape of the great wave curves around the deep trough below it, the two areas compete for attention, neither one possible without the other."

Alexander Calder's mobile sculpture Rouge Triomphant (Triumphant Red) (1959–63 Sheet metal, rod, and paint, 110 × 230 × 180 in) uses the literal physical phenomenon of balance to unify and animate his organic abstract shapes into a constantly shifting interactive sculptural composition.

The use of repetitive patterns to create an illusion of motion that deceives the eye forms the basis for Op art (short for Optical art). During the 1960s, painters in this style experimented with discordant positive– negative relationships. There is a noticeable sense of movement when we look at Cataract 3 (1967, PVA paint on canvas, 7’3 3⁄4” × 7’3 3⁄4”) by British artist Bridget Riley (b. 1931). If we focus on a single point in the center of the work, it appears there is an overall vibrating motion. This optical illusion grows out of the natural physiological movement of the human eye; we can see it because the artist uses sharp contrast and hard-edged graphics set close enough together that the eye cannot compensate for its own movement.

Pieter Bruegel, Hunters in the Snow, 1565. Oil on panel, 46 × 63¾"

"Rhythm gives structure to the experience of looking, just as it guides our eyes from one point to another in a work of art. There is rhythm when there are at least two points of reference in an artwork. For example, the horizontal distance from one side of a canvas to the other is one rhythm, and the vertical distance from top to bottom, another. So, even the simplest works have an implicit rhythm. But most works of art have shapes, colors, values, lines, and other elements too; the intervals between them provide points of reference for more complex rhythms. In Flemish painter Pieter Bruegel’s work, we see not only large rhythmic progressions that take our eye all around the canvas, but also refined micro-rhythms in the repetition of such details as the trees, houses, birds, and colors . All these repetitive elements create a variety of rhythms “all over.” In Hunters in the Snow, the party of hunters on the left side first draws our attention into the work. Their dark shapes contrast with the light value of the snow. The group is trudging over the crest of a hill that leads to the right; our attention follows them in the same direction, creating the first part of a rhythmic progression. Our gaze now traverses from the left foreground to the middle ground on the right, where figures appear to be skating on a large frozen pond. Thereafter, the color of the sky, which is reflected in the skaters’ pond, draws our attention deeper into the space, to the horizon. We then look at the background of the work, where the recession of the ridgeline pulls the eye to the left and into the far background. As a result of following this rhythmic progression, our eye has circled round and now returns to re-examine the original focal point. We then naturally inspect details, such as the group of figures at the far left making a fire outside a building. As our eye repeats this cycle, we also notice subsidiary rhythms, such as the receding line of trees. Bruegel masterfully orchestrates the winter activities of townspeople in sixteenth-century Flanders (a country that is now Belgium, The Netherlands, and part of northern France) in a pulsating composition that is both powerful and subtle at the same time."

The Pattern and Decoration Movement of the 1970s challenged several prejudicial conventions of the art world by emphasizing textile-like designs that lacked the self-conscious seriousness of modernvst painting, as well as techniques and materials that had been disparaged as "mere craft" or "women's work." We looked at Miriam Schapiro's Baby Blocks (1983. collage on paper. 29-7/8 x 30 inches) initially as an example of layered organic and geometric shapes, but it is also exemplary of the P&D movement.

Lari Pittman's Untitled #16 (A Decorated Chronology of Insistence and Resignation) (1993

Acrylic, enamel, and glitter on wood. 84 × 60 1/16 in.) extends the rhythmical patterning and inclusiveness of the P&D movement to create intricate narrative-rich compositions that incorporate other fringe elements of visual culture, including populist folk-art motifs, stock graphic design elements and corporate logos.

Degenerate Art, Socialist Realism, WPA murals, and Abstract painting

The bold colors, primitive draftsmanship and mythological potency of Emil Nolde's “Crucifixion” (1912. Oil on canvas) made it a major example of pre-WWI German Expressionism. Nolde was an early member of the Nazi Party, but in 1937 when - under the direct supervision of Modernism-hating failed artist Adolf Hitler - they put together the "Degenerate Art" exhibit, more of Nolde's works (including this one) were included than any other artist, and he was legally forbidden to paint.

In Seymour Fogel's 1938 WPA mural “The Wealth of the Nation,” the artist "looks at how state planning benefits us collectively. In this piece, we see a scientist peering into a microscope, an engineer examining blueprints, and a number of laborers performing industrial tasks." The morally uplifting message and easily understood pictorial style of this work was not far removed from the Nazi and Soviet artistic ideals.

Piero della Francesca's The Flagellation, c. 1469, a 23 x 32” oil and tempera painting on wood panel, achieves unity by balancing the geometrical precision of the architectural perspective against the organic forms of the human bodies and clothing, the deep spatial illusion on the left with the foregrounded figures on the right, and the dramatic emotional content of the flagellation with the calm and orderly overall structure and contemplative attitude of the three most prominent characters.

Joseph Cornell's Untitled (The Hotel Eden), 1945 (Assemblage with music box, 15⅛ x 15⅛ x 4¾”) is a strong example of both Conceptual unity - where the underlying ideas connect even if the formal qualities of the elements do not - and of the Gestalt principle of unity, whereby connections are left open, allowing the viewer to fill in the blanks, and arriving at a larger unity than suggested by its individual components.

"In his print “The Great Wave off Shore at Kanagawa,” Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) created a unified composition by organizing repetitions of shapes, colors, textures, and patterns to create a visual harmony even though the scene is chaotic. These repetitions visually link different parts of the picture. Even Mount Fuji, in the middle of the bottom third of the work, almost blends into the ocean: because whitecaps on the waves mimic the snow atop Mount Fuji, the mountain’s presence is felt and reiterated throughout the composition. The shape and placement of the boats also create a pattern amongst the waves. Because the great wave on the left is not repeated, it has a singular strength A that dominates the scene. Hokusai has also carefully selected the solids and voids in his composition to create opposing but balancing areas of interest. As the solid shape of the great wave curves around the deep trough below it, the two areas compete for attention, neither one possible without the other."

"The three similar diagrams above illustrate the idea of compositional unity. Although A is unified, it lacks the visual interest of B. While C is a unified work, its visual variety feels incoherent and chaotic. These diagrams show how too much similarity of shape, color, line, or any single element or principle of art can be monotonous and make us lose interest. Too much variety can lead to a lack of structure and the absence of a central idea. Experienced artists learn to restrict the range of elements: working within limitations can be liberating."

Amitayas mandala created by the monks of Drepung Loseling Monastery, Tibet, demonstrate the principle of radial symmetry. "Radial balance (or symmetry) is achieved when all elements in a work are equidistant from a central point and repeat in a symmetrical way from side to side and top to bottom. Radial symmetry can imply circular and repeating elements. Although the term “radial” suggests a round shape, in fact any geometric shape can be used to create radial symmetry. The Tibetan sand painting shown above is a diagram of the universe (also known as a mandala) from a human perspective. The Tibetan Buddhist monks who created this work have placed a series of symbols equidistant from the center. In this mandala the colors vary but the shapes pointing in four different directions from the center are symmetrical. The square area in the center of the work symbolizes Amitayus, or the Buddha of long life, and surrounds a central lotus blossom. The creation of one of these sand paintings is an act of meditation that takes many days, after which the work is destroyed. The careful deconstruction of the work after it has been completed symbolizes the impermanence of the world."

American artist Chuck Close (b. 1940) often uses motif (A design repeated as a unit in a pattern) to unify his paintings. In the above Self Portrait, (1997. Oil on canvas, 8’6” × 7’) Close uses a repeated pattern of organic concentric rings set into a diamond shape as the basic building blocks for his large compositions. These motifs, which appear as abstract patterns when viewed closely, visually solidify into realistic portraits.

Amitayas mandala created by the monks of Drepung Loseling Monastery, Tibet, demonstrate the principle of radial symmetry. "Radial balance (or symmetry) is achieved when all elements in a work are equidistant from a central point and repeat in a symmetrical way from side to side and top to bottom. Radial symmetry can imply circular and repeating elements. Although the term “radial” suggests a round shape, in fact any geometric shape can be used to create radial symmetry. The Tibetan sand painting shown above is a diagram of the universe (also known as a mandala) from a human perspective. The Tibetan Buddhist monks who created this work have placed a series of symbols equidistant from the center. In this mandala the colors vary but the shapes pointing in four different directions from the center are symmetrical. The square area in the center of the work symbolizes Amitayus, or the Buddha of long life, and surrounds a central lotus blossom. The creation of one of these sand paintings is an act of meditation that takes many days, after which the work is destroyed. The careful deconstruction of the work after it has been completed symbolizes the impermanence of the world."

Pattern, Rhythm, and Decoration

"Rhythm gives structure to the experience of looking, just as it guides our eyes from one point to another in a work of art. There is rhythm when there are at least two points of reference in an artwork. For example, the horizontal distance from one side of a canvas to the other is one rhythm, and the vertical distance from top to bottom, another. So, even the simplest works have an implicit rhythm. But most works of art have shapes, colors, values, lines, and other elements too; the intervals between them provide points of reference for more complex rhythms. In Flemish painter Pieter Bruegel’s work, we see not only large rhythmic progressions that take our eye all around the canvas, but also refined micro-rhythms in the repetition of such details as the trees, houses, birds, and colors . All these repetitive elements create a variety of rhythms “all over.” In Hunters in the Snow, the party of hunters on the left side first draws our attention into the work. Their dark shapes contrast with the light value of the snow. The group is trudging over the crest of a hill that leads to the right; our attention follows them in the same direction, creating the first part of a rhythmic progression. Our gaze now traverses from the left foreground to the middle ground on the right, where figures appear to be skating on a large frozen pond. Thereafter, the color of the sky, which is reflected in the skaters’ pond, draws our attention deeper into the space, to the horizon. We then look at the background of the work, where the recession of the ridgeline pulls the eye to the left and into the far background. As a result of following this rhythmic progression, our eye has circled round and now returns to re-examine the original focal point. We then naturally inspect details, such as the group of figures at the far left making a fire outside a building. As our eye repeats this cycle, we also notice subsidiary rhythms, such as the receding line of trees. Bruegel masterfully orchestrates the winter activities of townspeople in sixteenth-century Flanders (a country that is now Belgium, The Netherlands, and part of northern France) in a pulsating composition that is both powerful and subtle at the same time."

Acrylic, enamel, and glitter on wood. 84 × 60 1/16 in.) extends the rhythmical patterning and inclusiveness of the P&D movement to create intricate narrative-rich compositions that incorporate other fringe elements of visual culture, including populist folk-art motifs, stock graphic design elements and corporate logos.

Marcel Duchamp and the "Artist as Trickster"

Marcel Duchamp Fountain 1917

The most famous of Duchamp's Dadaist "readymade" sculptures, a store-bought mass-produced ceramic urinal turned upsidedown and signed with a fake name. Voted the most influential artwork of the 20th century. Here are two more readymades from Duchamp's classic early output:

Duchamp's final, secret installation Étant donnés (1946 - 1966) had been under construction for 20 years and was only unveiled after the artist's death. Mysterious, ominous, and emphatically engaged with 3D Renaissance illusionistic space, it was a final vexing prank on the cult that had grown up around his work and alleged retirement from art making.

Paul McCarthy, in his 1977 performance Grand Pop had, according to curator Ralph Rugoff, "settled on food products as his medium of choice, his trademark performance style crystalized. In actions that loosely allegorized social conditioning and sexual oppression, he stuffed raw meat and cold cream into his mouth; filled his pants with tuna fish, butter and ketchup; and dressed as a house wife and scrubbed the floor with milk." These and other transgressive gestures are clearly in line with the archetypal role of the trickster/artist as violator of social boundaries.

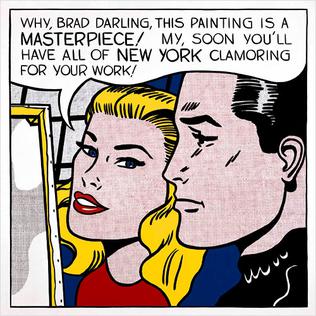

This postage stamp, commemorating the 1913 Armory Show in New York, uses the puzzled couple's reaction to Duchamp's Cubist/Futurist oil painting Nude Descending a Staircase, No 2 to represent the shock and skepticism with which the public received modern art, and woke Duchamp to the power of the trickster role.

Duchamp's final, secret installation Étant donnés (1946 - 1966) had been under construction for 20 years and was only unveiled after the artist's death. Mysterious, ominous, and emphatically engaged with 3D Renaissance illusionistic space, it was a final vexing prank on the cult that had grown up around his work and alleged retirement from art making.

Chris Burden Shoot 1971

Performance ("sculpture") in which the artist had a friend shoot him through the arm with a .22 rifle

Jeffrey Vallance Blinky the Friendly Hen 1978

Performance/artist book + 40 years of subsequent related work, all based on buying a frozen chicken at Ralph's supermarket and then paying for a full funeral for it at a pet cemetery in Calabasas

In one of his most famous performance art works, Beuys flew to New York, picked up by an ambulance, and swathed in felt, was transported to a room in the Rene Block Gallery. The room was also occupied by a wild coyote, and for the next three days, Beuys spent his time with the coyote in the small room, with little more than a felt blanket and a pile of straw. At the end of the three days Beuys was transported back to the airport via ambulance. He never set foot on outside American soil nor saw anything of America other than the coyote and the inside of the gallery.

Paul McCarthy, in his 1977 performance Grand Pop had, according to curator Ralph Rugoff, "settled on food products as his medium of choice, his trademark performance style crystalized. In actions that loosely allegorized social conditioning and sexual oppression, he stuffed raw meat and cold cream into his mouth; filled his pants with tuna fish, butter and ketchup; and dressed as a house wife and scrubbed the floor with milk." These and other transgressive gestures are clearly in line with the archetypal role of the trickster/artist as violator of social boundaries.

Trickster artist Maurizio Catellan has been in the news twice this semester - first when his Duchamp-inspired solid gold toilet entitled "America" (2016) was stolen from an exhibition in England, and this weekend when his 2019 banana-duct-taped-to-the-wall sculpture "Comedian" sold for $120,000 three times over at the Art Basel art fair in Miami, causing a huge public and media reaction, including being taken off the wall and eaten by a NYC performance artist.

The Yes Men's web/media interventionist prank "Dow Does the Right Thing" made the company's stock value temporarily plummet almost $3 billion. The collective utilizes a wide range of traditional and cutting edge media in a practice that combines the artist as trickster role with the idea of art as social activism.

Degenerate Art, Socialist Realism, WPA murals, and Abstract painting

The bold colors, primitive draftsmanship and mythological potency of Emil Nolde's “Crucifixion” (1912. Oil on canvas) made it a major example of pre-WWI German Expressionism. Nolde was an early member of the Nazi Party, but in 1937 when - under the direct supervision of Modernism-hating failed artist Adolf Hitler - they put together the "Degenerate Art" exhibit, more of Nolde's works (including this one) were included than any other artist, and he was legally forbidden to paint.

Richard Heymann's 1940 oil painting In Safe Hands is typical of the style of art the Nazis approved -- in fact this piece was purchased by Hitler himself.

Kazimir Malevich Suprematist Composition: Airplane Flying oil on canvas 1915

Although avant-garde artists such as Kasimir Malevich (above) were initially allied with the Bolshevik revolution in Russia, the increasingly totalitarian Soviet government also declared Modernist art to be unwholesome and self-indulgent, and officially forbade it. Boris Ieremeevich Vladimirski's Roses for Stalin (1949, Oil on canvas, 100.5 x 141 cm.) is typical of the kind of Socialist Realism painting that was deemed acceptable.

Franz Kline Puppet in the Paint Box 1940 oil on canvasboard, 14 x 18 inches

Partly in response to this association, and its implications about art, imagery, and propaganda, many of the WPA artists went on to form the famous post WW2 Abstract Expressionist movement, including Franz Kline, whose early work was rendered in a conventional illustrational style, but rapidly evolved to pure abstraction.

Franz Kline untitled 1948 Oil on collage on paperboard 71.3 x 56.4 ins

No comments:

Post a Comment